Fort Mose Historic State Park

Fort Mose Historic State Park

Differing Systems of Slavery

The Spanish system of slavery was different from our stereotypical understanding of American chattel slavery, which mimicked the more severe British system.

In Spain and her colonies, enslaved people were given certain rights. First of all, "slave" was a temporary title more than a life sentence — they could earn their own money and even buy their freedom. Spanish slaveholders were not allowed to separate families by selling them and could sue their masters in a court of law for mistreatment or neglect.

Sanctuary in Spanish Florida

In 1693, King Charles II of Spain signed a formal policy that offered sanctuary to people who were enslaved by the British. If these people were able to find their way to Spanish territory, they would be accepted as Spanish citizens.

However, this did not come free. People fleeing slavery were required to 1) convert to Catholicism; 2) join the Spanish militia or perform some government service; and 3) swear their fealty to the King of Spain.

Founded in 1738

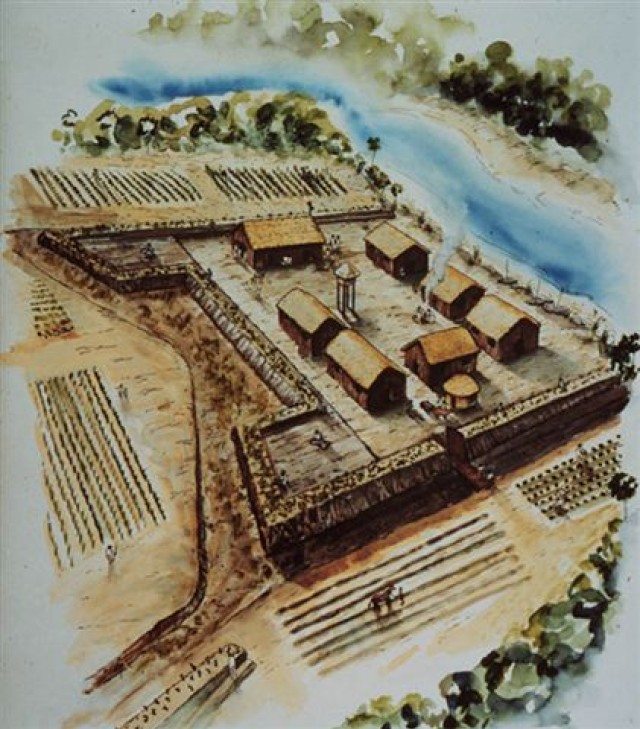

Fort Mose was officially established by Governor Manuel de Montiano in 1738. A stone fort was built on a site about two miles north of the Castillo de San Marcos, and the Black residents of the city established their homes outside of the fort.

After years of petitioning the Spanish king, Francisco Menendez was named the leader of Mose's town and militia. There was a Catholic priest assigned to the community, as well as a Spanish military officer. While the priest is recorded to have lived at Mose, it is not clear if the officer did, as well. It is likely that Captain Menendez was fully responsible for the community's day-to-day governance.

The Battle of "Bloody Mose"

James Oglethorpe, the British governor of Georgia, attacked St. Augustine by land and by sea in January of 1740. The residents of Fort Mose were evacuated to the Castillo de San Marcos with the rest of St. Augustine's citizens.

The militiamen of Mose, led by Captain Francisco Menendez, defended their settlement in a battle that British accounts called "Bloody Mose." Both the British and the Spanish armies were diverse in terms of race, with Africans, Europeans, and Indigenous people taking part in the invasion and defense of St. Augustine.

While this "Battle of Bloody Mose" resulted in a victory for the Spanish, the town and fortification of Mose was destroyed. Mose's townspeople and militiamen moved into St. Augustine and lived alongside the city's European residents.

The Second Fort Mose

After nearly twelve years of living within the walls of St. Augustine, the Black residents of the town were moved back to the site of Fort Mose and ordered to build a new fort. Though reluctant to leave the city, Captain Francisco Menendez

The First Spanish Period Ends

In 1763, Spain was on the losing side of a conflict called the "French and Indian War" or the "Seven Years War." In order to keep control of Cuba, Spain gave Florida over to the British and abandoned the colony. The residents of Fort Mose evacuated with the Spanish, knowing that if they stayed, they would surely be re-enslaved by the British.

Preserving the Story

The site where Fort Mose once stood was used for military purposes by British and American forces for decades after the end of the First Spanish period. Gradually, though, the ever-changing shorelines of Florida's waterways turned the site into muddy marshland, and Fort Mose became something that only existed in historical documents.

Generations of researchers, including Zora Neale Hurston, Kathleen Deagan, and Jane Landers, have dedicated themselves to recovering this unique story of American history. Their steadfast efforts resulted in the "re-discovery" of the Fort Mose archaeological site in the late 1980s.

Visiting Fort Mose

The Fort Mose Historical Society was founded in 1997 by a dedicated group of citizens who still oversee the interpretation that occurs at Fort Mose Historic State Park. Through their collaboration with the Florida State Parks service, Fort Mose is still a site of education and cultural events. Visit the Fort Mose Historical Society Website by clicking here.

Fort Mose Historic State Park has been recognized as a National Historic Landmark since 1994. In 2009, the National Park Service titled Fort Mose as a precursor site of the National Underground Railroad Network.

This 24-acre state park offers nature trails and other outdoor amenities, allowing the site's beauty to emphasize its unique and powerful history. Several panels throughout the park trails share information about the historical and natural resources of the area. The Visitor's Center museum contains artifacts, maps, video and audio content, and interactive displays.

Resources

Online Resources

Read about Fort Mose on the National Park website by clicking here.

Further Reading

Atlantic Creoles in the Age of Revolution, by Jane Landers

Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose: A Free Black Town in Spanish Colonial Florida, by Jane Landers

“The Atlantic Transformations of Francisco Melendez,” by Jane Landers, which appears in Biography and the Black Atlantic

Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stone Rebellion, by Peter Wood