Peek into 1870s St. Augustine with this article, which is part fiction / part travel guide.

One of Lincolnville's oldest buildings, built in 1885.

Home of Mrs. Rena Ayers, Civil Rights Housemother.

Home of nurse Mrs. Janie Price.

Home of Loucille Plummer, unwavering activist.

Historically Black Street in North City.

Home of the Reddicks, local leaders.

Former residence of Willie Galimore.

Home of Reverend and Mrs. Halyard, community leaders.

Former SCLC headquarters.

Home of local civil rights leader.

Oldest congregation in Lincolnville.

Previously the Lincolnville Public Library.

First documented Christian bride in the United States.

Florida's first Civil Rights museum.

Commemorates the night of June 9, 1964.

This African-American owned bookstore focuses on the literature of the African diaspora.

In an age shaken by revolutions, the fight for Black freedom stretched across the Caribbean and affected Florida in unexpected ways.

Florida's first Black general.

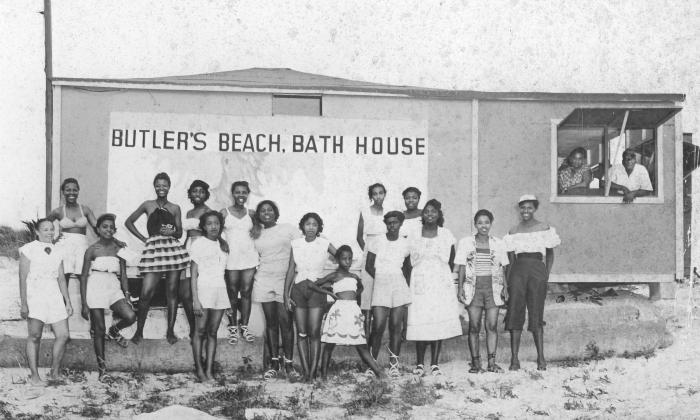

Entrepreneur and founder of historic Butler Beach.

Resort founded during Jim Crow Era.

Leader during the Second Seminole War.

Center of defense and heritage.

The most prominent Black Seminole leader.

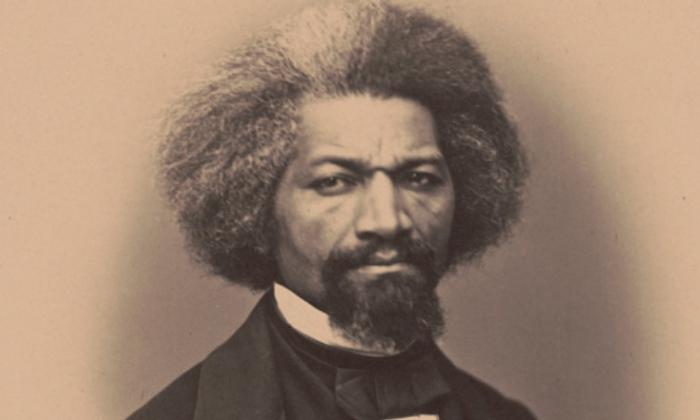

Writer, abolitionist, and political leader.

Lincolnville hub during Civil Rights Movement.

One of the city's oldest structures.

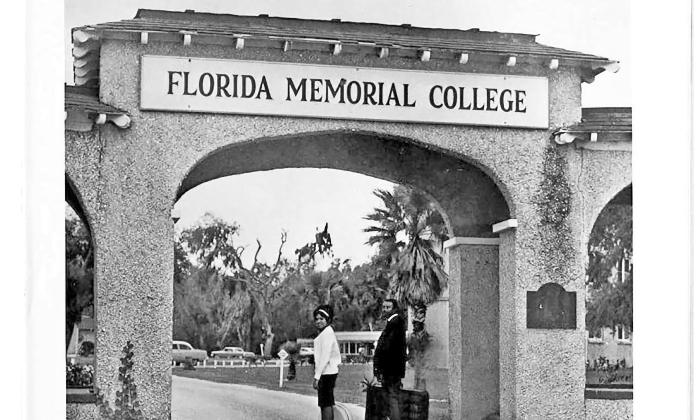

Historically Black College that once stood in St. Augustine.

The National Parks Service's official guide to Fort Matanzas National Monument.

The original destination of the Underground Railroad.