Castillo de San Marcos

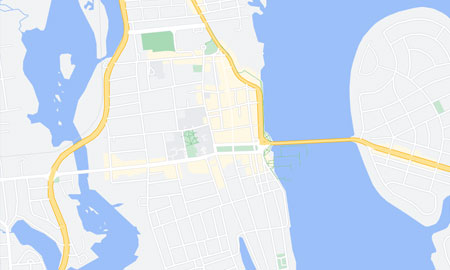

(904) 829-6506 On the bayfront, north of the Bridge of Lions.

1 South Castillo Dr.

St. Augustine, FL 32084

Closed Thanksgiving Day and Christmas Day. Ticket booth closes at 4:45 p.m.

The Castillo de San Marcos, the oldest masonry fort in the continental United States, is a large Spanish stone fortress built to protect and defend Spain's claims in the New World. It is a National Monument, more than 327 years old, and is the oldest structure in St. Augustine.

History of Castillo de San Marcos

The Spanish began constructing the Castillo de San Marcos in 1672 and completed it in 1705 after 23 years. Many Spanish forts preceded the Castillo. However, this is unique because it was made of coquina, which made the structure fire-resistant and impenetrable to enemy attack.

The fort came under fire for the first time in 1702. British forces, led by General Moore, burned the city but could not penetrate the Castillo's walls. Subsequent attacks in 1728 and 1740 yielded similar results, and the British were never able to take the Ancient City by force.

In 1763, Florida became a British colony with the signing of the Treaty of Paris, and stayed under English rule for 20 years. The Castillo was used as a military prison during the Revolutionary War, and at one time, it held three signers of the Declaration of Independence within its walls.

At the end of the Revolutionary War, Florida was returned to Spain in 1784, and it became a United States Territory in 1821. The Americans called the Castillo "Fort Marion," honoring the revolutionary patriot from the Carolinas, General Francis Marion. The United States government used Fort Marion as a prison for Native Americans in the late 1800s. Natives from both Florida and the Great Plains were held at the fort during this time.

The fort was officially removed from the active list of fortifications in 1900 and was preserved and recognized as a national monument in 1924. Congress renamed the fort in 1942, reverting to the Spanish name, the Castillo de San Marcos.

Amenities at Castillo de San Marcos

- Self-guided tours (free with admission)

- Cannon firings / weaponry demonstrations (free with admission) — Saturdays and Sundays at 10:30 a.m., 11:30 a.m., 1:30 p.m., 2:30 p.m., and 3:30 p.m.

- Restroom facilities

- Gift shop

Camping, fishing, bicycling, and skating of any sort are prohibited. Check the Castillo's website for more details on what is permitted on and around the grounds.

Visit Castillo de San Marcos

Admission: $15.00 for adults ages 16 and older. Free for children ages 15 and younger. Additional information and tickets may be purchased at the booth or the fort's website.

Address: 1 South Castillo Drive, St. Augustine, Florida 32084

Parking: A parking lot with an hourly fee is on the grounds of the fort. The Historic Downtown Parking Facility is a 10-minute walk from the site.

Other Parks Near Castillo de San Marcos

There are other parks nearby to enjoy, including Anastasia State Park and Fort Mose. See our local Parks Directory and the article "Experiencing Living History" to learn more.

Free Park Days

The National Park Service offers free entry on Free Park Days

On 10 days in 2026, the National Park Service provides free entry to U.S. citizens and residents:

- February 16, 2026: President’s Day

- May 25, 2026: Memorial Day

- June 14, 2026: Flag Day

- July 3–5, 2026: Independence Day weekend

- August 25, 2026: 110th birthday of the National Park Service

- Sept. 17, 2026: Constitution Day

- Oct. 27, 2026: Theodore Roosevelt’s birthday

- November 11, 2026: Veterans Day

Upcoming Events

| Event | Date | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Weekend Cannon Firing | Today, February 15th, 2026 | 10:30 am - 3:30 pm |

| Weekend Cannon Firing | Saturday, February 21st, 2026 | 10:30 am - 3:30 pm |

| Weekend Cannon Firing | Sunday, February 22nd, 2026 | 10:30 am - 3:30 pm |

| Weekend Cannon Firing | Saturday, February 28th, 2026 | 10:30 am - 3:30 pm |

| Weekend Cannon Firing | Sunday, March 1st, 2026 | 10:30 am - 3:30 pm |

| Weekend Cannon Firing | Saturday, March 7th, 2026 | 10:30 am - 3:30 pm |

| Weekend Cannon Firing | Sunday, March 8th, 2026 | 10:30 am - 3:30 pm |

| Weekend Cannon Firing | Saturday, March 14th, 2026 | 10:30 am - 3:30 pm |

| Weekend Cannon Firing | Sunday, March 15th, 2026 | 10:30 am - 3:30 pm |

| Weekend Cannon Firing | Saturday, March 21st, 2026 | 10:30 am - 3:30 pm |

Castillo de San Marcos

(904) 829-6506 On the bayfront, north of the Bridge of Lions.

1 South Castillo Dr.

St. Augustine, FL 32084

Closed Thanksgiving Day and Christmas Day. Ticket booth closes at 4:45 p.m.

Admission | Ticket Prices

All tickets valid for seven consecutive days.| Option | Price |

|---|---|

| Adults (16 years and older) | $15.00 per person |

| Children (15 and under) | FREE if accompanied by an adult |