Is St. Augustine THE Nation's Oldest City?

St. Augustine claims many firsts—and most of them are legitimate.

A tale of history, food, and competing claims

Once you've moved to St. Augustine, you're bound to realize that we have an obsession with our age. Not our personal ages, the age of our city and many of her parts. That obsession is reflected in the number of appellations the town and region frequently use: "First Coast," "Ancient City," and "Oldest City." (And don't get me started on the use of "Historic," as in "Florida's Historic Coast." The ubiquitous use of "historic" makes it sound as if everything in St. Augustine is historic and that's not true.)

We've even named our businesses in this manner. In St. Augustine, you can find a long list of companies under "A for Ancient," such as the Ancient City Brunch Bar, Ancient City Gymnastics, Ancient City Slingshots, and Ancient City Accounting. Similarly, under "O for Oldest" we can find Oldest City Insurance, Oldest City Bait and Tackle, and (my personal favorite) the billboard that used to proclaim "Oldest City Dentist." (Why anyone would want to be known as the oldest city dentist is beyond me.)

Beyond the naming, we have the claiming of numerous firsts:

- The Cathedral Basilica is the oldest Christian Parrish in the U.S.

- Fort Mose is the first legally sanctioned free black settlement in the U.S.

- Potter's Wax Museum is evidently the first wax museum in the U.S.

- Aviles Street is the oldest street in North America. This claim is contested by not one, but two cities. First, Leyden Street in Plymouth, Massachusetts was laid out by the pilgrims in 1620 and called, appropriately, First Street. Second, Philadelphia claims that Elfreth's Alley is the longest continuously inhabited residential street in America, with at least one home completed by 1703. Aviles Street in St. Augustine was part of the original layout of our city and we have documentation that the Catholic Church was along this street from 1572 until 1702. Unless we want to quibble on residential vs. business districts (and Philadelphia clearly does), Aviles Street is the oldest street in the U.S.

- Finally, here's the biggest and most controversial claim: There are scholars who claim that St. Augustine is the home of the first Thanksgiving for Europeans in America. (More on this later, because it's just so delicious!)

Is this true? Is what we call the "Ancient City" really the oldest city in America?

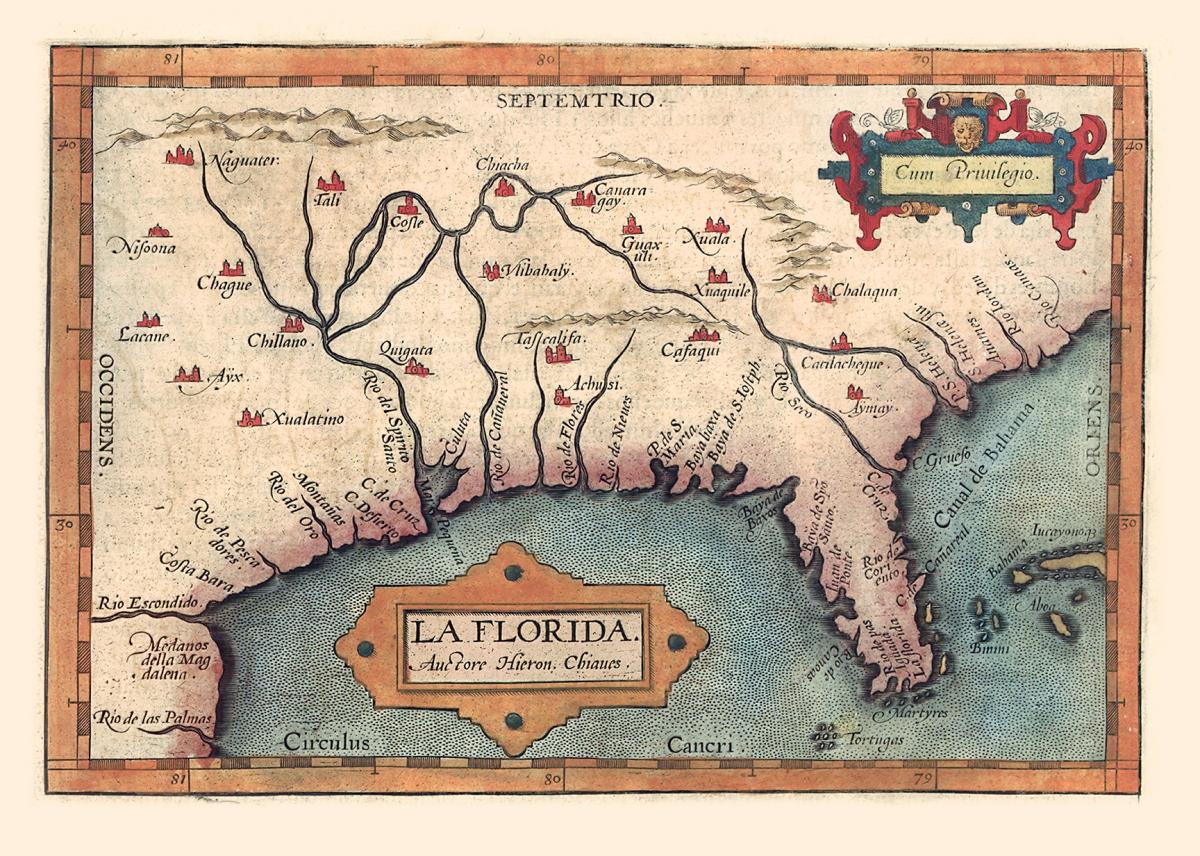

Kind of, if we take a few liberties. First of all, I do think the use of the word "ancient" should be reserved to describe truly ancient cities and settlements in the old and new worlds. After all, Cadiz, Spain was founded in the 1200s, and the people of Timucua had a thriving settlement in what is now St. Augustine 500 years before Menéndez stepped ashore. A city less than 500 years old hardly qualifies as "ancient." Calling St. Augustine the "Ancient City" seems hyperbolic to me.

Secondly, the British, French, and Spanish didn't "discover" the new world. The Wampanoag people had settled in what we know as Massachusetts more than 10,000 years before the pilgrims landed. The Seminoles, Timucuans, Calusa, and Tequesta tribes had organized societies throughout Florida long before Menéndez landed on Saint Augustin's Day in 1565.

So what about those oldest and first claims?

The competitors are Jamestown, Plymouth, and St. Augustine.

Jamestown was founded 42 years after St. Augustine and, as one historian noted, a St. Augustine settler could have become a grandparent in the time between St. Augustine's founding and Jamestown's founding. Jamestown is out of the running anyway as ultimately the town and government moved to what is now known as Williamsburg in 1699.

If one delves into various online articles, instead of calling Plymouth the oldest permanently inhabited settlement in the new world (as was done when I was in grade school), Plymouth is known as the oldest permanently inhabited English settlement in the new world.

So that leaves St. Augustine. Yes, we who live here can proudly claim to be residents of the oldest continuously inhabited European city in America.

And that brings us back to Thanksgiving

As for the Thanksgiving claim, it depends on what one celebrates.

The pilgrims celebrated Thanksgiving in November of 1621, a year after landing, sharing the area's bounty and their harvest with the natives who had helped to teach them many of the survival skills they needed. The Wampanoags brought at least five freshly killed deer to the feast and the pilgrims provided fowl, vegetables, and seafood. The pilgrims had two strikes against them when they arrived. First, they landed on Cape Cod in December after 66 days at sea. (This was unfortunate as most voyages from England to America's coast took 60 days, so I certainly think they left a bit late in the year.) Second, the pilgrims were town people and notoriously not suited to life in the wilderness. It's no wonder that, in addition to seeking help from the Wampanoags, a contingent from Plymouth sailed up to a settlement in the Sheepscot River in Maine to beg for provisions, which were freely given. The pilgrims relied more on the kindness of strangers than did the Spanish settlements.

More than 50 years prior, on September 8, 1565, the Spanish held a thanksgiving mass a few weeks after having landed safely in la Florida. Admittedly a "mass of thanksgiving," is an event that Catholics host often to celebrate things such as a priest's confirmation, a young girl's quinceañera, or reaching shore after a perilous voyage, while the pilgrims' Thanksgiving was a celebration after a very difficult year in the "New World."

Still, Menendez hosted a Thanksgiving "feast" in 1565—a feast that largely consisted of the same foods those aboard the San Pelayo had eaten during their crossing: garbanzo beans, salted pork, hardtack, and red wine. We do know that the Timucuans were present and assume they also contributed to the meal. If so, they might have added meat in the form of turkey, venison, or gopher tortoise; seafood, and vegetables they had grown. As a former cruising sailor I can categorically state that, once ashore, no sailor considers their passage food a feast, so I assume Menéndez and his contingent were delighted with the local offerings.

Celebrating the St. Augustine Thanksgiving

This photo was provided by Florida's Historic Militia, Jackie Hird, photographer.

Today, we St. Augustinians gather for Thanksgiving along with the rest of the U.S., on the third Thursday of November; while we celebrate Founder's Day on a Saturday near September 8, the day Pedro Menéndez named our city after Saint Augustin. Menéndez first made landfall in "la Florida" on August 28, 1565, Augustin's Feast Day, and 11 days later held a thanksgiving mass—our country's first Thanksgiving, the one with salt pork and hardtack. In modern St. Augustine, the Founding Day Celebration starts with the landing at Mission Nombre de Dios, and continues with a procession to the Fountain of Youth, where they reenact the first Thanksgiving in the U.S.

The Thanksgiving Feast

A local scholar has suggested that we in the Oldest City could claim the honor of "First Thanksgiving," while feasting on our nation's traditional menu of turkey, stuffing, cranberry sauce (or jellied cranberry), green bean casserole, and pies. And most do. Those who wish to celebrate the holiday with a St. Augustine flair, can find a number of local cookbooks that offer recipes from many settlers in what is now St. Augustine—from the Timucuans to the Spanish, Minorcans, British, and 20th-century American church ladies.

One book, currently available in local shops, is Food Favorites of St. Augustine, by Joan Adams Wickham. She actually offers a garbanzo soup recipe, which would be close to how the garbanzo beans and salt pork were prepared in 1565. However, Joan's version is certainly more flavorful as she has added the potatoes, peppers, onions, and garlic—items that may have been lacking after a sea journey.

Joan reminds us that corn, beans, and squash comprise the "trinity of Indian foods," and offers various recipes for corn, squash, squash blossoms, and beans. Many of her recipes are "reading recipes" with few measurements and sparing words—the kind of recipes that have been passed down by someone's grandmother.

Everything below is verbatim from Joan Adams Wickham's cookbook. ¡Buen provecho!

Spoon Bread

Spoon Bread is one of the most famous southern dishes and traces its origin to the Indian porridge, "suppawn."

Preheat oven to 425 degrees.

Put 5 tablespoons butter in a medium-size earthward casserole or other baking dish and place in oven to melt while you prepare the batter.

Combine 1 cup of water-ground, yellow or white corn meal with 1 teaspoon salt in a mixing bowl and stir in 2 cups boiling water until smooth. Let stand for a few minutes, then stir in 1 cup of cold milk.

Add 4 eggs, one at a time, beating well after each addition.

Stir in the melted butter last. A pinch of nutmeg or mace may be added before the butter.

Pour into the hot baking dish and bake for 25 to 30 minutes.

Serve hot in the baking dish with plenty of extra butter.

Roast Pork Spanish Style

Make slits all over a 6-pound loin of pork and insert 2 garlic cloves cut into slivers.

Mix salt, pepper, and a generous pinch of oregano, rub this over the pork.

Preheat oven to 450 degrees and place pork on a rack in pan in oven.

When roast begins to brown, turn oven down to 350 degrees.

Baste pork frequently with lime or sour orange juice. The slight garlic flavor and crust, crisp and sour, makes this a better than best tasting roast.

Allow 30 to 45 minutes per pound; pork demands thorough cooking.

Garnish roast with spiced peaches.

Serve with a salad of grapefruit sections and Spanish onion rings with olive oil and lemon juice dressing.

Spanish Wine Jelly

Soak 2 packages plain gelatin in 1/2 cup water, then dissolve in 3/4 cup boiling water.

Add 1 cup sugar and stir until dissolved; then add 1/4 cup lemon juice, 1 cup orange juice, and 1 cup best sherry wine.

Pour into small molds. Chill until firm.

Sweet Potato Pie

You will need one 9-inch unbaked pie shell.

Cook enough sweet potatoes and sieve to make 1 1/2 cups of puree.

Add 1 cup of brown sugar, 2 tablespoons of light molasses, 1 teaspoon each of cinnamon and ginger, and 1/4 teaspoon each of salt, cloves, and nutmeg.

Mix in 3 slightly beaten egg yolks and 1 cup milk, and 1/2 cup cream, scalded together.

Add 2 ounces Puerto Rican rum.

Fold in 3 stiffly beaten egg whites.

Pour into an unbaked pie shell.

Bake in a 400 degree oven for about 40 minutes, or until a knife blade inserted near the center comes out clean.

A note about my choices:

- Spoon Bread is a more modern version of the Timucuan porridge, "suppawn."

- Pork was a staple meat for the Spanish and subsequent farmers, including the Florida Crackers.

- Spanish Wine Jelly strikes me as a much better version of the ubiquitous holiday jello salads.

- Sweet Potato Pie represents all of the sweets and treats that were absent from either of the early Thanksgivings, where they, sadly, had no pie.

The painting of our nation's first Thanksgiving was one that had been on exhibit at the Governor's House. We thank them for the use of this photo.