The Birthplace of African American History

Historian, David Nolan, explains the importance of St. Augustine’s African American heritage.

Foreword

Most tourists are familiar with the prominent events of St. Augustine's history: the landings of Juan Ponce de Leon and Pedro Menéndez, the sieges on the Castillo de San Marcos, and the arrival of Henry Flagler — but what about the stories that you haven't heard? Those of Francisco Menéndez's resilience at Fort Mose, and Jorge Biassou's boldness as general? Or Isabel de los Rios's entrepreneurship, and Barbara Vickers's strong spirit? St. Augustine is filled with marvelous, unheard stories — one only needs to scratch the surface.

David Nolan is the main historian for the first Civil Rights Museum in Florida, the ACCORD Civil Rights Museum, and was a founding trustee of the Fort Mose Historical Society, which is the Community Support Organization for Fort Mose Historic State Park. Mr. Nolan has also aided in research at the Lincolnville Museum and Cultural Center. He has long been invested in sharing the history of St. Augustine with the public and we thank him for his contribution.

"The Birthplace of African American History" by David Nolan

The rich African American heritage of St. Augustine should cause all history textbooks to be rewritten. When the Spanish conquistador Pedro Menendez founded St. Augustine in 1565, not only were there Black members of his crew, but he noted that his arrival had been preceded by free Africans in the French settlement at Fort Caroline, just a few miles north.

Our oldest written records, the Cathedral Parish Archives, list the first birth of a Black child here in 1606 — 13 years before many textbooks say that the first Black people on these shores arrived at Jamestown in 1619.

The first legally recognized community of ex-slaves (freed people) was Fort Mose, the northern defense of St. Augustine, founded in 1738 to protect the city from British invasion. In 1740, when General James Oglethorpe attacked from Georgia, it was the Battle of Fort Mose that proved decisive in turning him around and sending him back from where he came. The site of this free Black fort is now recognized as a National Historic Landmark and is run by the Florida Park Service. It is considered the focal point for the first Underground Railroad, which ran not from south to north, but rather from the British southern colonies farther south into Spanish Florida, where formerly enslaved people would be given their freedom.

Battle of Bloody Mose in 1740, painted by Jackson Walker.

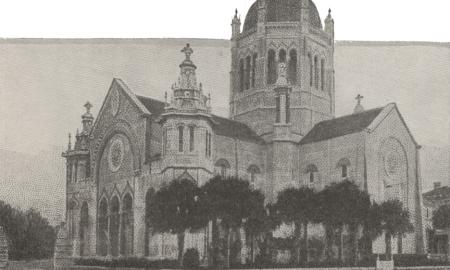

Everyone has heard of General Colin Powell, but two centuries before him there was a Black general in St. Augustine. His name was Jorge Biassou, and he was one of the original leaders of the slave uprising in Haiti in the 1790s. In the twists and turns of international politics, he became a Spanish general. He was sent to St. Augustine in 1796, as the second-highest paid official of the colony, and stayed here until his death in 1801. His funeral was held at the Cathedral Basilica on the Plaza downtown, and he is buried in Tolomato Cemetery on Cordova Street.

A Black militia saved St. Augustine from invasion at the time of the War of 1812, and its members were awarded land grants in gratitude by the Spanish governor.

Black people played an important role in relations with the Seminole Indians. A free Black man named Antonio Proctor served as an Indian interpreter for the first American governor of Florida. A century and a half later one of his descendants, Henry Twine, was active in the Civil Rights Movement and became the first Black vice mayor of St. Augustine.

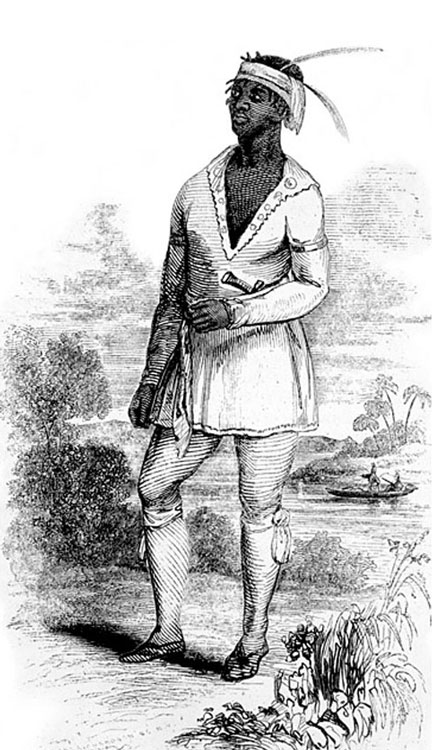

John Horse, a Black Seminole.

Other Black people lived within the Seminole Nation and rose to high positions there. A Black man named Abraham was sometimes called "the prime minister of the Seminoles." Another Black Seminole, John Horse (pictured, above), played a prominent military role in the Indian wars of the 1830s.

During the Civil War, Black St. Augustinians served in both the Union and Confederate armies. Their graves can be found in many of our historic cemeteries. Harriet Tubman, the famed "conductor" of the Underground Railroad, accompanied the Union soldiers who came down the St. Johns River during the war.

The famed abolitionist, Frederick Douglass, spoke here in 1889 at Genovar's Opera House on St. George Street. (There is a marker at the site.)

Former slaves (freed people) established the community of Lincolnville in 1866 in the southwest peninsula of St. Augustine. Lincolnville is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, in part because of its origins, in part because given its time of development — it includes the greatest concentration of treasured Victorian architecture in the Ancient City, and in part because it was the launching place for demonstrations that led directly to the passage of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Lincolnville Museum and Cultural Center exhibits the dynamic history of this community.

St. Augustine played a major role in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. Demonstrations began here with a sit-in at the local Woolworth's lunch counter in 1960 and grew to a crescendo by 1964 when Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. led his last major campaign that resulted in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 — one of the two great legislative accomplishments of that movement. Dr. King went on from here to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. A street running through the heart of Lincolnville has been named in his honor.

Martin Luther King, Jr. being escorted from the Grand Jury in St. Johns County, 1964. (Image courtesy of Florida Memory.)

There is a Freedom Trail of the Civil Rights Movement's historic sites, honoring local heroes like Dr. Robert Hayling, dentist and organizer, and the St. Augustine Four (young teenagers who spent six months in jail and reform school for trying to order a hamburger at the Woolworth's lunch counter).

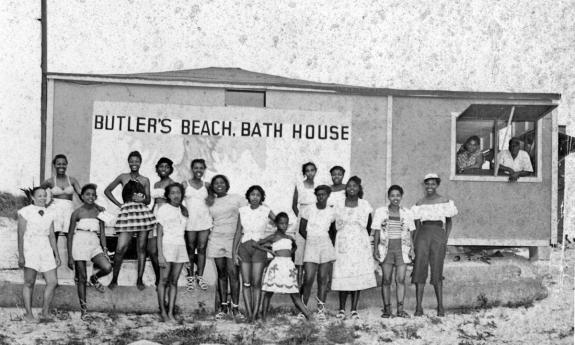

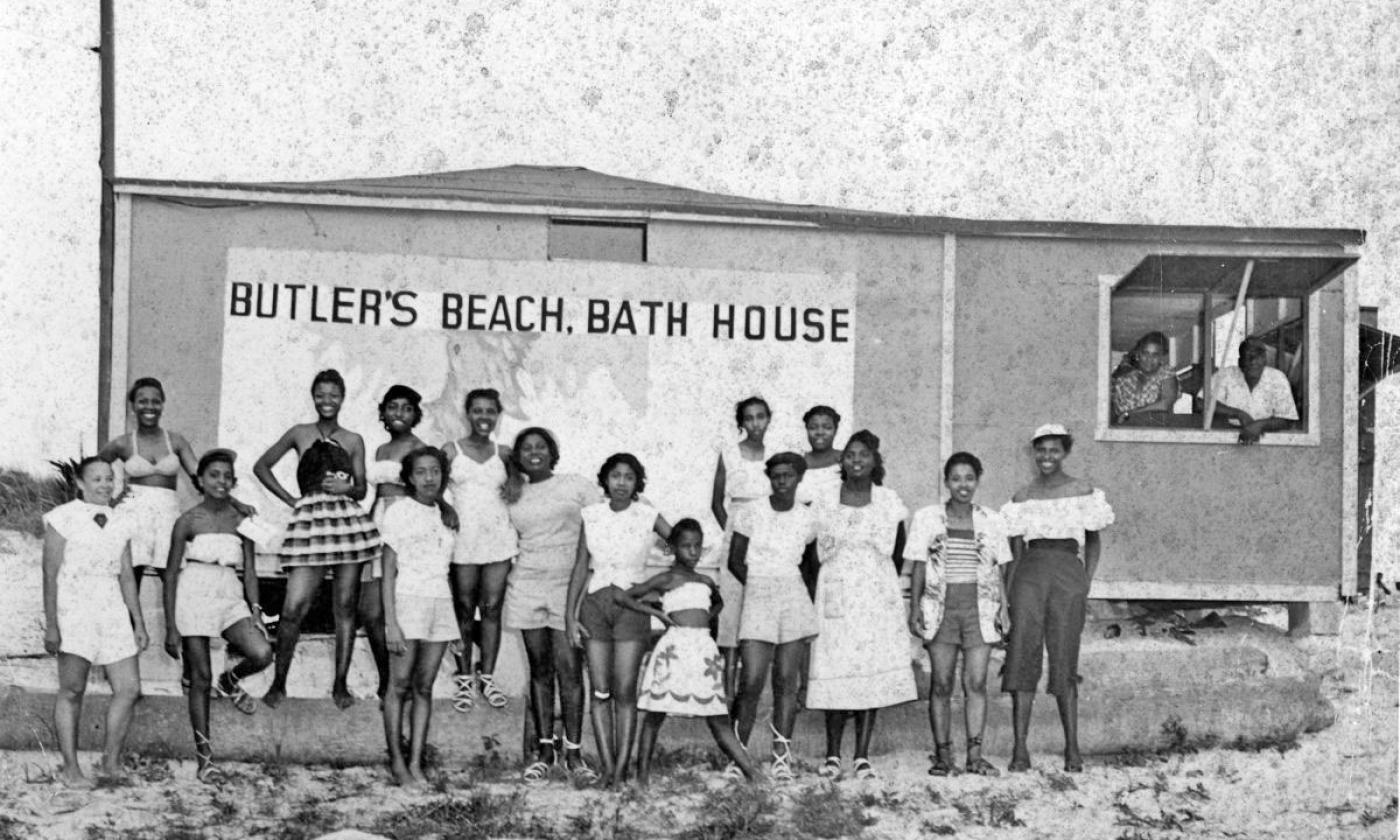

A thriving Black business district grew up along Washington Street in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Frank Butler, the leading businessman, also developed Butler's Beach on Anastasia Island, one of the historic Black beaches of Florida from the age of segregation. He also had real estate holdings in West Augustine around the Florida Normal (later Florida Memorial) College campus, a Black school — and St. Augustine's first college — that was located here from 1918 until 1968. The internationally celebrated novelist Zora Neale Hurston was among its teachers. There is a historic marker at the house at 791 West King Street where Hurston lived.

Your visit to St. Augustine is incomplete without exploring the rich African American heritage that changed our nation's history and inspired the world.

Afterword

Whether you're exploring St. Augustine for the first time, returning for a visit, or being a tourist in your own hometown, it makes a visit all the more meaningful when you know the Ancient City's history. We hope you enjoy St. Augustine in a new light with the stories that are finally being explored and shared.

To read a comprehensive guide to the locations that tell these stories, go to the article titled, Visiting Black History Museums.

(Foreword and Afterword written by Cheyenne Koth.)